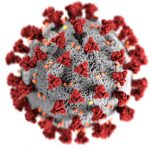

Why has Slovakia, a small open economy, done so well with low mortality rates in response to the crisis? And what to do now in face of an expected huge recession? Some insights from an interview with top policy advisor Martin Kahanec.

Some core messages of the interview:

- Slovakia has done a tremendous job stopping the spreading of the virus, for instance the low mortality rate put the country at the very last place in the ranking in Europe.

- The success can be traced back not so much to a rigorous, but to a fast and effective response.

- But the Slovak economy is paying a huge price for the shutdowns in the country and among the trade partners.

- Income maintenance schemes to strengthen the demand side and measures to preserve liquidity to grease the wheels of the economy are essential for a fast recovery.

- My role in the advisory body of the Slovak government is to evaluate crisis management procedures and risks and assess possible measures and their effects.

GLO Fellow and GLO Cluster Lead “Labor Mobility” Martin Kahanec (Central European University and Bruegel) is also the Director of the Slovak Think Tank CELSI. He was just appointed by his government to the Slovak COVID-19 Economic Crisis Council. He reports on the Slovak experiences and the way to recovery.

Middle photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

Interview

GLO: How well did Slovakia get through the COVID-19 crisis in terms of infections and death cases?

Martin Kahanec: Slovakia has done a tremendous job stopping the spreading of the virus. After more than 11 weeks since its first case of COVID-19, recorded on March 6, 2020, as of 25 May 2020 Slovakia had only 1,513 cases (of which only 163 active). Its 5 deaths per million inhabitants (28 in total) put Slovakia at the distant last place in the ranking of European countries by this mortality measure. For comparison, during the same period (eleven weeks into the pandemic) similarly-sized Ireland recorded more than 16 times as many cases and more than 55 times as many deaths and Denmark more than 7 times as many cases and nearly 20 times as many deaths. In spite of local outbursts in care homes and marginalized Roma settlements, the “first wave” of the pandemic in Slovakia was only a wavelet, as the country has to date recorded only 6 days with more than 50 new cases.

For the record, this result is not an issue of (the lack of) testing or isolation of the country: per million of inhabitants Slovakia has done fewer tests than Denmark, but more than Sweden, France, or the Netherlands, and just about as many as Finland. Slovakia is a small open economy with a very busy international transportation system, and the share of cross-border workers is the highest in Europe, at about 5.2% of its labor force – many of whom work in care homes and touristic resorts in Austria and northern Italy. Slovaks spend on average more nights abroad than Czechs, Italians, or Spaniards. Bratislava and Vienna are among the closest national capitals in the world, just about 65 km apart, Czechia is about the same distance from Bratislava, and Hungary, just like Austria, share borders with Slovakia.

GLO: Is this success the result of a more rigorous Slovak response strategy?

Martin Kahanec: Perhaps not as much rigorous as speed. Within ten days since the first case, Slovakia had shut down schools (in Bratislava within less than a week), introduced mandatory face masks in public transportation (first in Europe), closed non-essential shops, introduced border controls and mandatory quarantine for people returning from abroad (within a week), and shut down international air as well as bus and train passenger services. An important factor has been the impressive compliance of the general public, with face masks becoming the norm immediately, with politicians and television celebrities as well as news anchors leading by example and wearing facemasks on all occasions. Several mistakes have been made, but overall the system of measures has worked effectively.

GLO: What were the consequences in terms of GDP losses?

Martin Kahanec: Slovakia is paying a hefty price for the shutdowns in the country and among our trade partners. Primarily due to weakened foreign demand, in Q1 2020 Slovak GDP shrank by 3.9% y-o-y, which was one of the largest drops in Europe. Fitch has downgraded Slovakia from A+ to A on May 8. In April 2020 the unemployment rate increased by 1.38 percentage points y-o-y. On the other hand, the government is now gradually removing the restrictions, and the automotive sector, one of the backbones of the Slovak economy, is rebounding, with the four large car making plants in Slovakia (VW, PSA, Kia, Land Rover) gradually returning to their capacity.

GLO: What can be done to foster a fast recovery?

Martin Kahanec: During the trough of the crisis the government should help those who have been hit the hardest and lost their livelihoods. This moral obligation is strengthened by the fact that keeping especially the workers with the highest risks of spreading the virus at home reduces the negative externality their continued activity would inflict on the rest of the society and that, for this reason, some sectors were shut down directly by the government. For a swift recovery, as soon as the epidemiological situation permits, workers should be allowed to return to jobs and children to schools. Effective testing, tracing, and isolating of the cases is needed to avoid a possible second wave.

Income maintenance schemes to strengthen the demand side and measures to preserve liquidity to grease the wheels of the economy are essential. For Slovakia, as a small open economy, coordination with its key trading partners and, especially, at the European level is of key importance.

But it is important to understand that the crisis will make some products, services, or even sectors obsolete, and it will open new opportunities and avenues for innovative economic activities at the same time. Therefore, what will matter in the long run is how the measures adopted will facilitate the reallocation of resources to the most promising economic endeavors, rather than cementing them in those, which have no economic future.

GLO: You have been just appointed to the Slovak COVID-19 Economic Crisis Council; what is the role of this council?

Martin Kahanec: The Economic Crisis Council is a temporary advisory and coordinating body at the Ministry of Finance during the COVID-19 crisis. Its purpose is to evaluate crisis management procedures and risks for the development of the Slovak economy and assess possible measures and their effects. We elaborate on specific proposals in response to the economic crisis caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic in Slovakia.

*************

With Martin Kahanec spoke Klaus F. Zimmermann, GLO President.

The Journal of Population Economics welcomes submissions dealing with the demographic aspects of the Coronavirus Crisis. After fast refereeing, successful papers are published in the next available issue. An example:

Yun Qiu, Xi Chen & Wei Shi (2020): Impacts of Social and Economic Factors on the Transmission of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China, GLO Discussion Paper, No. 494.

REVISED DRAFT NOW PUBLISHED OPEN ACCESS ONLINE: Journal of Population Economics, Issue 4, 2020.

Further publication on COVID-19 of a GLO DP:

GLO Discussion Paper No. 508, 2020

Inter-country Distancing, Globalization and the Coronavirus Pandemic – Download PDF

by Zimmermann, Klaus F. & Karabulut, Gokhan & Bilgin, Mehmet Huseyin & Doker, Asli Cansin is now forthcoming OPEN ACCESS in The World Economy doi:10.1111/twec.12969 PREPUBLICATION VERSION

More from the GLO Coronavirus Cluster

Ends;