Will happiness levels return to normal before the end of 2020? Talita Greyling and Stephanié Rossouw of GLO analyze the situation, as it happens – real-time happiness levels and emotions (www.gnh.today) during the evolution of the Coronavirus Crisis. The Gross National Happiness data set used (a real-time Happiness Index) is an ongoing project, the two researchers launched in April 2019 in South-Africa, New-Zealand and Australia. The project is presented below and documents the development of real-time happiness in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa in the periods of the outbreak of the Coronacrisis in those countries.

The authors

Talita Greyling: School of Economics, University of Johannesburg, South Africa, and GLO; email: talitag@uj.ac.za

Stephanié Rossouw: Faculty of Business, Economics and Law, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand,and GLO; email: stephanie.rossouw@aut.ac.nz

Stephnie Rossouw

Talita Greyling

The analysis

Traditionally, economists measured the well-being of people or a nation by using objective economic indicators such as gross domestic product (GDP). We know that these indicators do not measure well-being per se, but merely specific conditions, which is believed to lead to a good life. What we should be measuring is whether people’s lives are getting better? In general, when people are happy and satisfied with their life, it signals that they have a higher level of well-being.

Gross National Happiness (GNH) refers to the level of happiness for a group of citizens or nations and the best-known surveys that captures cross country data are the Gallup World Poll Survey data and World Value Survey data. In these surveys we find measures of subjective-wellbeing, thus evaluative happiness, which if averaged across a country gives the mean subjective well-being of a specific country. Although these measures of subjective well-being are very useful and informative there are significant time-lags between real-time events and the reporting of this evaluative happiness levels. What is needed is a real-time measure of happiness.

Using social media and the voluntary information sharing structure of Twitter, Greyling and Rossouw (in collaboration with AFSTEREO) have been determining the happiness in real-time (mood) of citizens in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa since April 2019 (http://gnh.today/), and lately also been analyzing the specific emotions of Tweets, distinguishing between eight emotions, anger, anticipation, disgust, fear, joy, sadness and surprise.

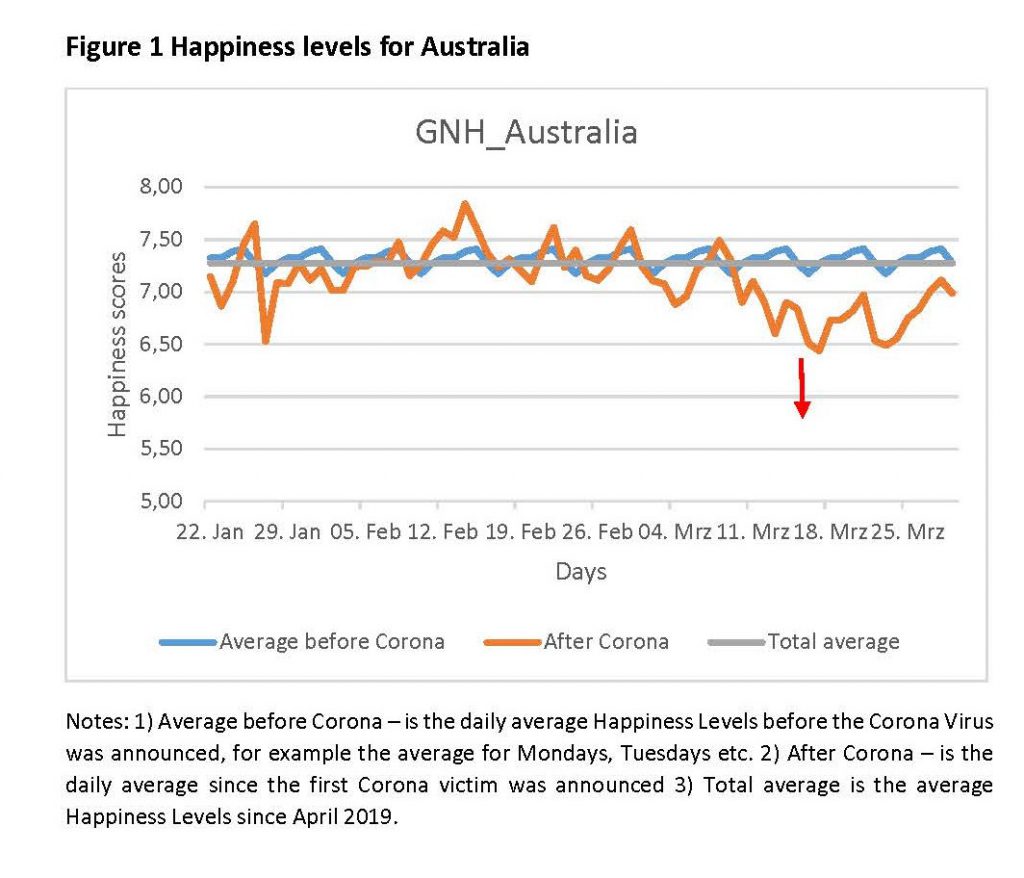

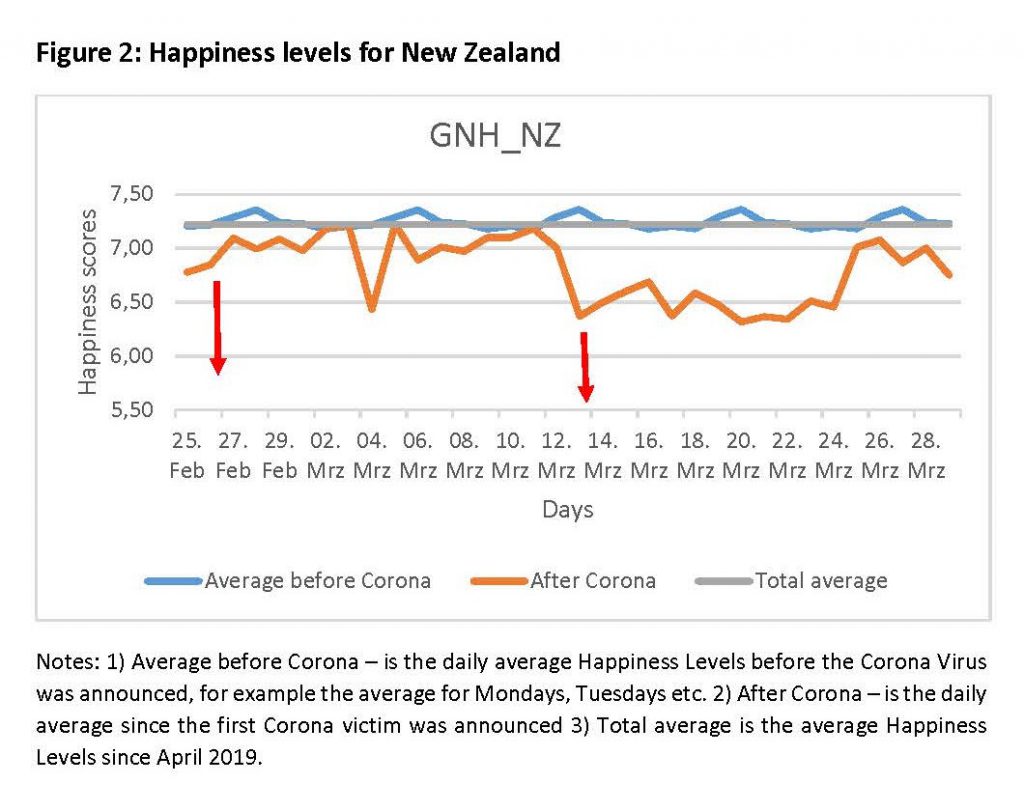

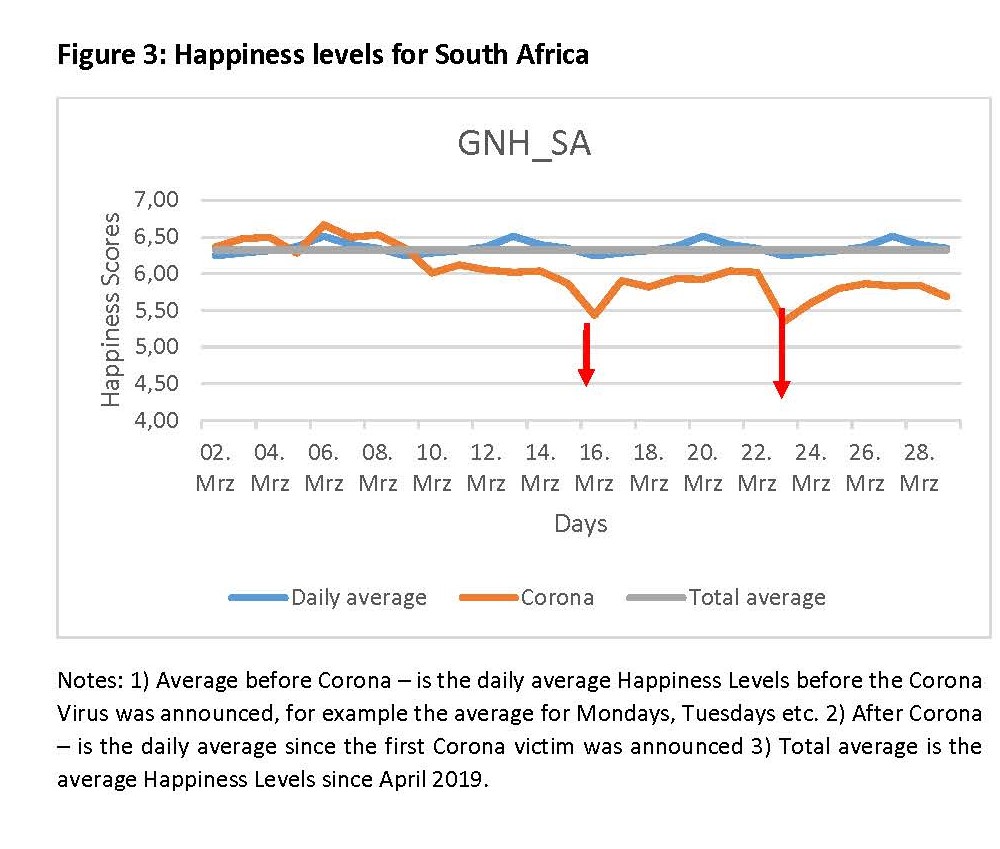

They analyze extracted Tweets using sophisticated software to determine the sentiment and the emotions of the Tweets. Sentiment analysis is used to label a ‘live’ stream of tweets of these countries as having either a positive, neutral or negative sentiment after which a sentiment balance algorithm is applied to derive a happiness score. The scale of the happiness scores is between 0 (not happy) and 10 (very happy), with 5 being neutral, thus neither happy nor unhappy. In this manner, they have been tracking the ‘mood’ of these nations and analyzed the impact of various economic (industrial actions), political (national elections), social (death of Kobe Bryant and COVID-19, xenophobia, music concerts) and sport events on happiness levels, as early as one hour after it happened. See Figures 1-3 for a peek into what the happiness index can ascertain.

As can be seen from Figure 1, on 25 January when Australia confirmed its first COVID-19 case, there was very little reaction. Happiness even increased somewhat after the announcement, though the higher levels of happiness were related top sport events. The dip in the happiness on 27 March was due to the death of the American basketball player, Kobe Bryant’. On 17 March when Prime Minister Scott Morrison banned gatherings larger than 100 people, we for the first time saw a significant decrease in the happiness levels. The Australians are not on complete lockdown, but it seems that their happiness levels continue to stay below pre-Corona times. We will be tracking these changes in the coming weeks, to see if the happiness levels return to pre-Corona levels as time goes by.

Coincidentally, until the outbreak of COVID-19, the lowest happiness level in New Zealand was on 27 January (6.43), also signalling New Zealander’s empathy with Kobe Bryant’s death. As can be seen from the Figure 2, on 28 February when New Zealand confirmed its first COVID-19 case, there was very little reaction. On 4 March, New Zealand experienced the ‘Toilet paper apocalypse’, but it wasn’t until 13 March that the lowest level of happiness (6.37) was recorded. People were devastated by all the concert and festival cancellations, because of COVID-19. The first day of complete lockdown was on 26 March. We will be monitoring whether New Zealanders adjust to their new normal over the coming weeks.

As can be seen from Figure 3, on 6 March when South Africa confirmed its first COVID-19 case, the happiness level was above the average for the period preceding the outbreak, as well as the total average. It wasn’t until 16 March when reality set in for most South Africans after President Cyril Ramaphosa declared a national state of disaster, that we saw a decrease in happiness levels. When the announcement came on 23 March, that a complete lockdown of South Africa will commence on 27 March, the index fell to its lowest level yet (5.35). We will be monitoring whether South Africans adjust to their new normal over the coming weeks.

Technical Support by AFSTEREO

Reference

Greyling T. & Rossouw S. 2020. Gross National Happiness Project. Afstereo (IT partner). University of Johannesburg (funding agency). Pretoria, South Africa. www.gnh.today.

Ends;